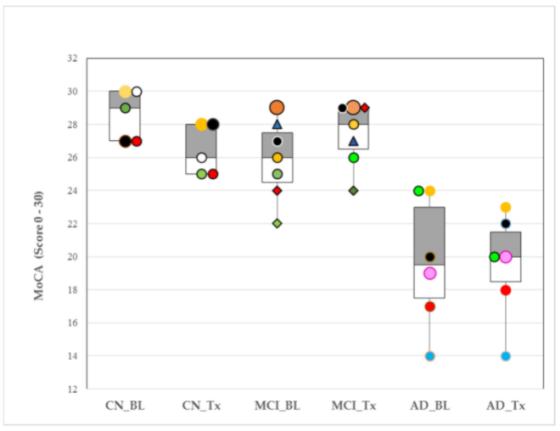

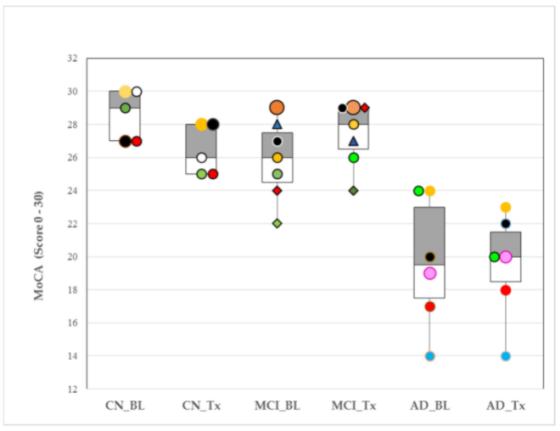

This figure shows changes in cognitive assessment scores for individuals in each group (CN=cognitively normal, MCI=mild cognitive impairment, AD=Alzheimer’s disease) at the start of the study and after 4 weeks.

Dental Device for Snoring May Slow Onset of Alzheimer’s Disease

Center for BrainHealth

This figure shows changes in cognitive assessment scores for individuals in each group (CN=cognitively normal, MCI=mild cognitive impairment, AD=Alzheimer’s disease) at the start of the study and after 4 weeks.

Share this article

Sandra Bond Chapman, PhD

Chief Director Dee Wyly Distinguished Professor, School of Behavioral and Brain Sciences Co-Leader, The BrainHealth Project

Jeffrey S. Spence, PhD

Director of Biostatistics

This pilot study investigates the relationship between respiration rate and snoring in individuals with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease.

This review of cognitive research supports the theory that noradrenaline is a protective factor against Alzheimer's disease.